Titi Mary Tran/ Nguoi Viet English

Alvin Nguyen, Donny Pham, Cathy Duong and Long Ho are four of thousands of high school seniors in California who are graduating this month. At first glance, this group of Vietnamese American high school students seems to resemble a cast of model valedictorians at their high schools.

They have high grade-point averages. They’ve been accepted to elite colleges and universities. They are loyal and obedient and loyal children at home. The thought of Asian American students is that they are high achievers who come from successful families with hard-driving parents who are wired for learning.

These students don’t fit that stereotype. Instead, their stories depict a tale of many trials.

Duong comes from a low-income family that includes sister with developmental disabilities who need her help and care. Pham uses gardening at school to help him de-stress and refocus. Ho, who has two sisters and three brothers, overcame his own anxiety by forcing himself to meet new people. And Nguyen, who achieved a perfect math score on his SAT exam, diligently practiced problems using free, online educational resources for months before the test.

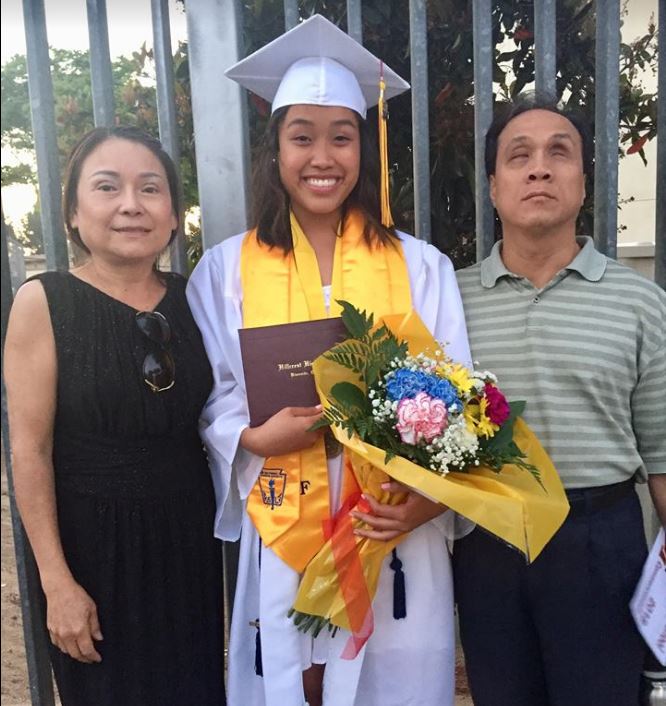

And then, there is Waverly Ninh, an average student from Hillcrest High School in Riverside, the only one of the group who isn’t a class valedictorian or holder of the highest GPA.

These teens belong to the Vietnamese American generation that knows nothing about the Vietnam War, except for what they read in a few pages in a chapter in their high history text books. They are different from their parents, who often are categorized into waves. The refugee wave. The boat people wave. The humanitarian operation wave. The immigrant wave. The family-sponsored wave. The international students wave.

As they graduate, these young adults are reflecting on the trials, the errors and the sacrifices that their elders made. They share in the insights and concerns of Generation Z in mainstream American culture.

Family’s help meets helping family

Their struggles are different from those their parents went through, but the same resourceful that helped their elders through their worries have helped this batch of young adults to overcome their obstacles.

Nguyen will graduate Wednesday from Ocean View High School in Huntington Beach with a 4.8 GPA, the highest possible at the school. He’s the student who used free online tools such as Khan Academy to achieve that perfect SAT math score.

“It was recommended by a friend and it has a SAT training sections. I spent a few months on that and at least 30 minutes a day doing problems, and it was a really big help,” Nguyen said.

While Nguyen is proud of his high GPA and SAT score, Waverly Ninh was hesitant to reveal hers. Through family connections, Ninh took private classes to prepare her for the SAT. But instead of deciding to attend a four-year school like Nguyen, who will attend UCLA, Ninh opted for community college near her home.

Her reason? “To save money,” Ninh said.

The estimated annual cost for an in-state student to attend a University of California campus in 2017-18 was $34,700. One year at Yale University, a private institution, was $67,620.

The real obstacle for Ninh are time and family responsibilities. Ninh lives with her parents and her grandmother. Her father is blind and her mother works full-time, so she is expected to help run the house. Living away from home isn’t an option.

“I wish I had better time management. Sometimes, family interferes with my work. I have to cook and usually start the homework late,” Ninh said.

Duong echoed the same “time management” sentiment as Ninh, but she found her Academic Decathlon family at Garden Grove High School. What she learned in that environment helped her ascend to Yale, which she will enter this fall and has numerous scholarships to bring the cost down to about $4,000 a year. She graduates from high school on Thursday.

“People see this Academic Decathlon club as the nerdiest thing, but in there I found a learning family, and others who love learning, love to grow. It helps me with public speaking, and it allows me to be vulnerable. It helps club members to inspire each other, help each of us to work harder and be ourselves,” Duong said.

Family expectations to help out with the chores does not exist with the male teens. In fact, the issue did not come up as a concern for Nguyen, Pham and Ho. When asked, the three brushed aside the question as if it were something trivial. Perhaps there is a gender bias in such expectation among Vietnamese parents.

Expectation and career choices

Though their college of choice is different ― Alvin Nguyen to UCLA, Donny Pham (Santiago High School) to UCI and Long Ho (Bolsa Grande High School) to Princeton ― all three young men have chosen to major in computer science in college. They all used non-traditional methods of education such as the online free resources, to get where they wanted to go.

Unsurprisingly, Duong and Ninh choose English/pre-med at Yale and nursing at community college, respectively.

This raises a question as to whether male and female high school students are encouraged or conditioned to pursue more traditional majors that fit gender stereotypes among Vietnamese Americans, both at home and at school.

Perhaps.

According to a 2018 study by the American Educational Research Journal, women are less likely to pursue certain fields where they need to study more or science. That isn’t because they can’t do the work, but instead because of the potential for gender discrimination in those careers.

Whatever path they follow, best of luck, Class of 2018. Hard work will continue to pay off.